As a child I thought that I would be Leonardo da Vinci when I grew up. Not that I would aspire to his fame and greatness–I merely thought it was a job, like being an engineer, a teacher, an accountant. Classify clouds, watch the eddies dance in streams, invent weaponry and mechanical devices to do work, sketch horses and hands–this was a job worthy of pursuing!

Growing up in Singapore disabused me of this fancy very quickly. By the time we were 14 we had to be ‘streamed’ into the arts or the sciences. And of course, the prestige and utility were in the sciences. Out of 320 plus students in my year, 40 were picked to be in the science class and although technically one could choose which stream to be in, it was a given that the top 40 students would opt for science. Our subjects from then on were general mathematics, calculus, biology, physics, chemistry, a second language and the token arts subject, literature (to keep us ‘well-rounded.’) No Leonardo da Vinci job for me!

There has always been this perceived dichotomy between the arts and sciences. Once you picked a path the other was closed to you; one was either good in science or the arts. It’s an easy way to categorize someone: a person in the sciences is presumably logical and objective while artists are emotional and subjective in their thinking. No, artists don’t even think, they merely feel. They are flamboyant, fanciful and flippant. In the practical, pragmatic world of Singapore, what use was an artist?

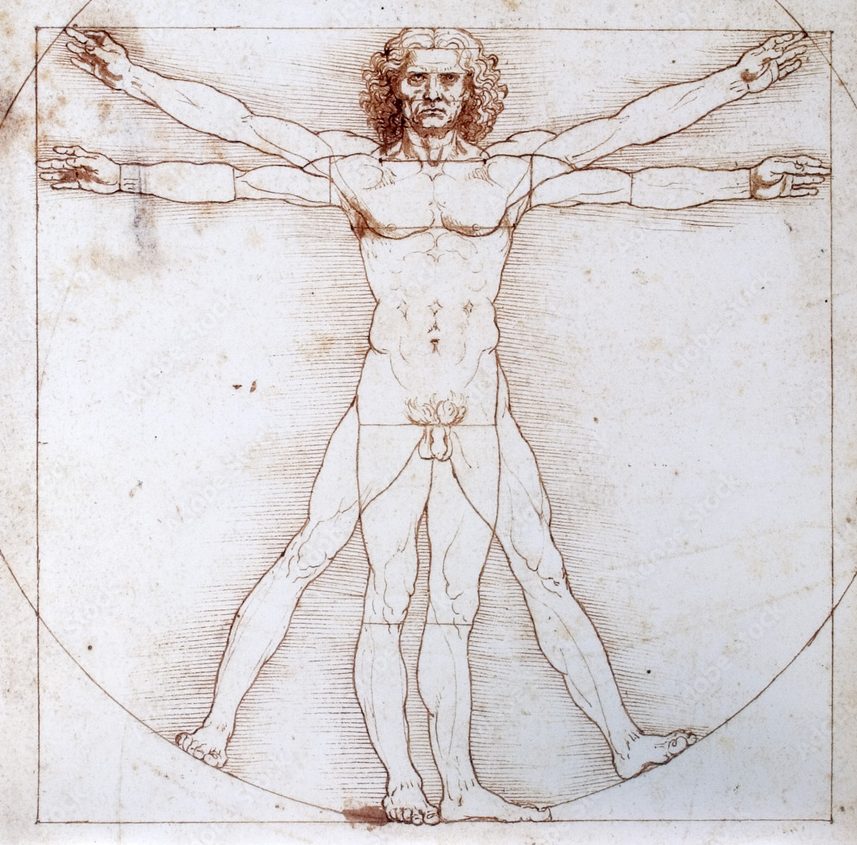

The reason I wanted Leonardo’s job was that I saw its unifying principle. The scientist and artist both organize and order the world. Both rely on the empirical, based on observation and experience. Both test or ‘trial’ the world through repeated practice or sequences. Both seek to quantify, qualify and testify to our existent universe. Their approaches and modalities may differ but then the combination of these would only provide more options for testing and ordering out of chaos. Science and art are humankind’s means of resisting entropy and the void. They are how we interpret the world.

One tool shared by both the arts and the sciences is that of the question. Excellence in science or the arts starts with the quality of questions posed in deciphering the world. Poor questions lead to dull science and hackneyed art. A well formulated question works just as well as a diamond-edged tool in both fields. What would one see if one chased a light beam? Pursuit of such a question leads to the possibilities of poetry and scientific theories.

We shouldn’t have to choose one field or the other, especially not at such a young age. Over-specialization occurs too early in many education systems. For true creativity and innovation to develop we need to embrace as many ways of seeing as possible, we need flexible minds that can toggle between worlds and amalgamate them. In essence, we need to teach a mental alchemy that can take the dross materials of the world and out of them create brilliance: Fiat Lux!